It began as it usually does. In my early 30s, as my body slowed down and the rhythms of my life began to settle, I started going to the gym, and eventually began paying more attention to how I dressed.

In my teens, I was always suspicious of appearances – it seemed shallow, always felt out of place. I was not comfortable in my own body, so the idea of self-expression was an alien concept. Considering the music I listened to, it made sense to wear all black, if possible, I always understood it as a placeholder, a practical way to sidestep the necessities of fashion.

The process began as you might expect. After a slow-building mish mash of generally appropriate brands – Uniqlo, Weekday, maybe some COS – I made a Pinterest board to accumulate and study references, eventually filtering what I had found to achieve something closer to myself.

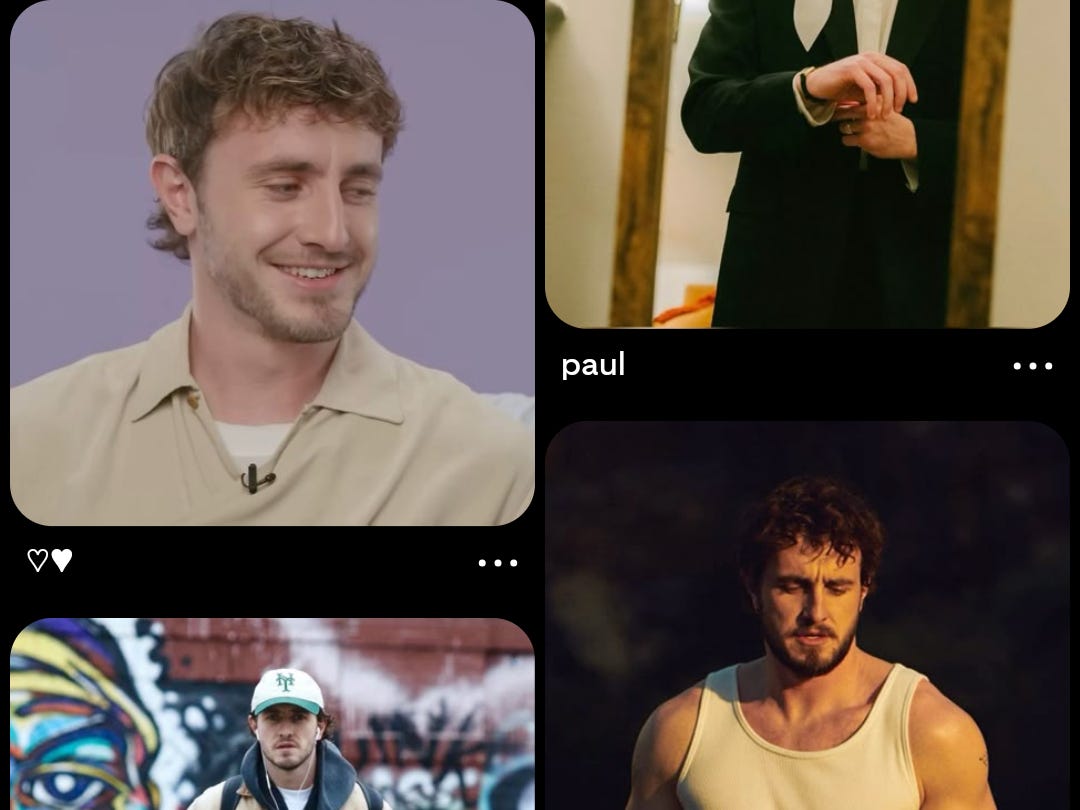

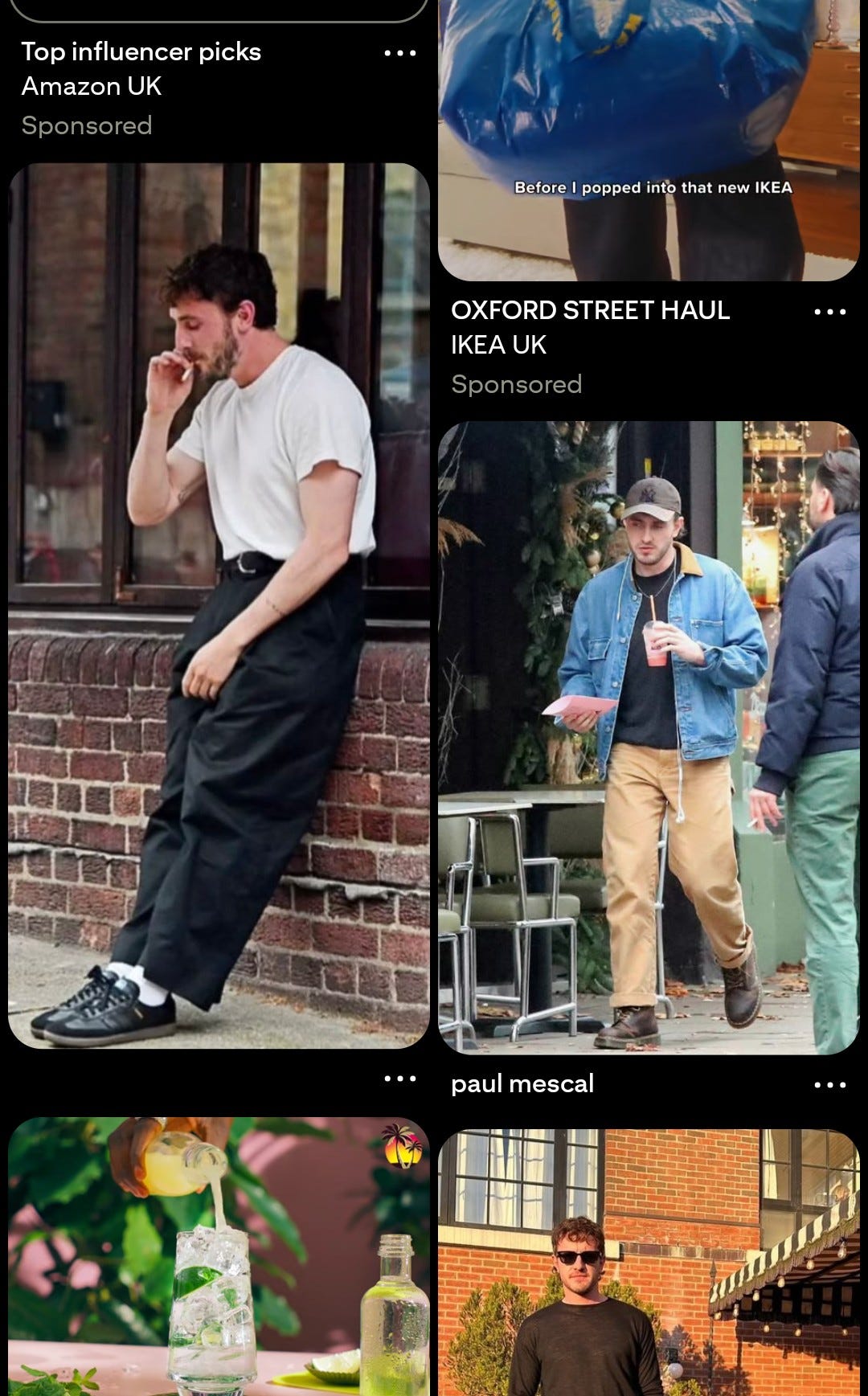

Male fashion, as is often noted by writers on the subject, is more about the navigation of subtle codes than the flashy statements of eye-catching decoration or garish colours. Think a well-made white T-shirt with some hint of structure. A pseudo-neutral palette anchored in either beige or navy. As I continued, something strange began to happen. Among the archive of understated and functional minimalist basics I was amassing, a recognisable figure kept appearing – appearing again and again in different yet familiar outfits. Pale skin. Wide shoulders. Clad in the uniform of a late-20s, early-30s East London resident. There was Paul Mescal.

Unlike his counterparts – say, the more queer-baiting, fashion-forward Timothée Chalamet – Paul was casual yet sophisticated. He’s the tidied-up version of 21st-century masculinity: muscular but sensitive, comfortable and clean-cut. This is not to suggest he is indistinct. But it’s worth noting that his two most notable fashion-related moments – the silver chain he wore in Normal People and the oft-discussed, shorter-than-average shorts – weren’t exactly his decisions. The necklace was mentioned by Rooney in the original book, and his original shorts that drew attention were just GAA shorts – one is a production note, the other cultural expression.

But he is not an unwitting participant. In a GQ vox pop, he articulated a rationale for how the ‘proportions’ of the shorts work with a longer shirt. This is a small example of a larger point: contemporary male fashion is less about sophisticated navigation of code than it is about an authentic one.

Perhaps taste is better left unspoken; fashion is something worn, lived, performed. The great anxiety underpinning a conscious, explicit engagement with appearance is not that it is dishonest, but that it is revealing. Laid bare, we are less original than we might assume. The desire to be accepted flattens the self in the face of a greater collective identity. In the end, we all become our parents.

‘The very word “personality,” JC Flugel notes in The Psychology of Clothes, ‘implies a mask, itself an article of clothing.’ Scrolling through Pinterest becomes its own form of rapid-fire mask-wearing – one image and then another, mostly forgettable, until one, surprising even to myself, stands out and solicits attention. The self is something discovered and performed, then discarded for another that fits better.

I like how others look. On the street, a parade of people walk by: a man returning home from work, wearing an office-blue shirt bland enough for a corporate context, yet somehow empty enough to suggest he has more going on in the rest of his life; a woman out for a walk in the evening sun, casually dressed, perhaps popping outside after working from home all day – creating a necessary break between working and resting in the same space. Others are dressed badly, oddly, all of it is totally fantastic.

It can seem as if social codes come more easily, more naturally, to them, but I simply have no expectation beyond what they present – a cliché, an archetype, a weirdo, it all blurs into the patterns of life and sociality. Individuality happens amid the stew of collectivity; we are only ourselves by contrast and complement.