Behold! The anchovy

A history and future of the humble fish; a cheesy 80s movie plot; a climate disaster and recovery.

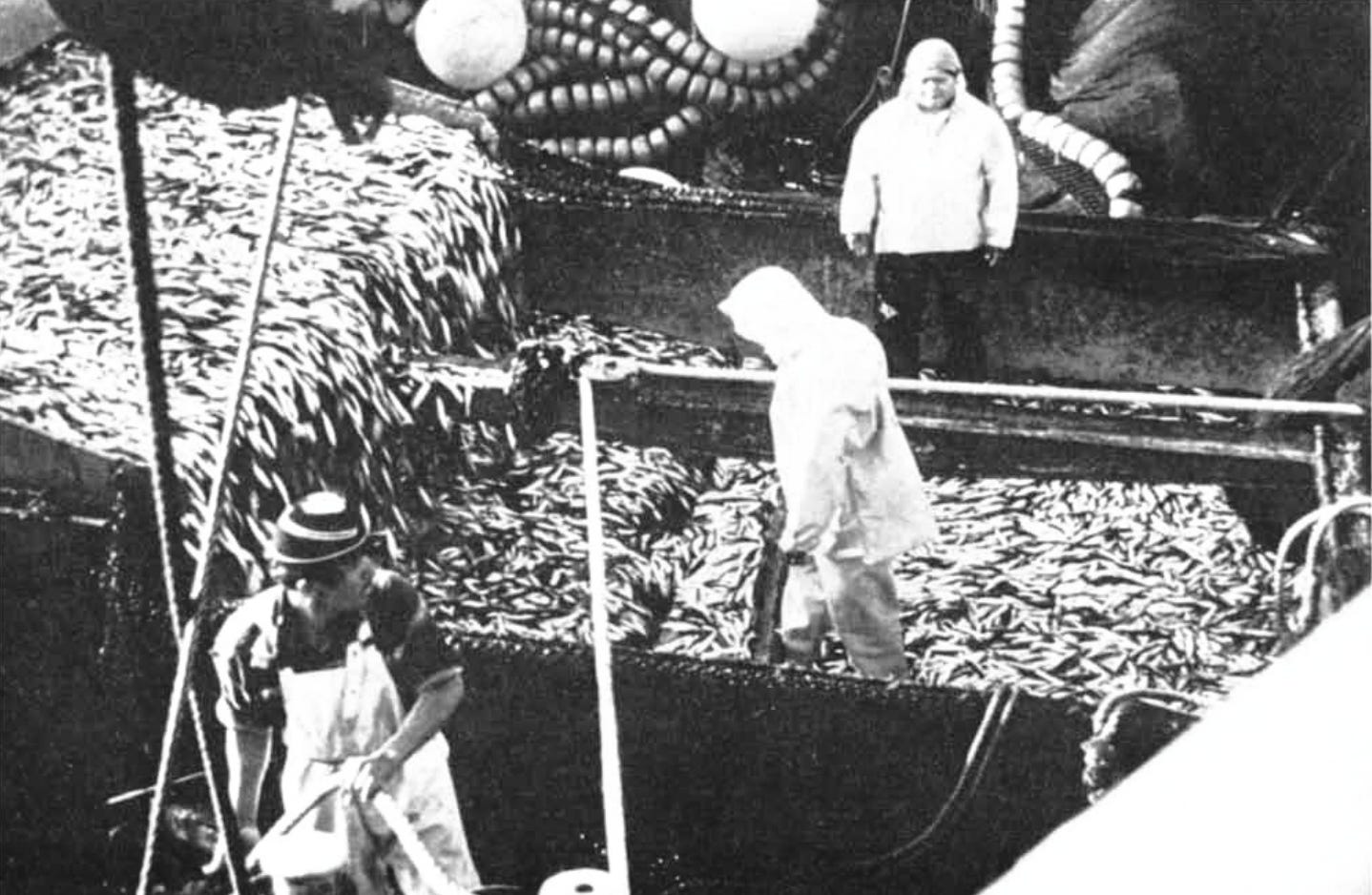

Peruvian fishing trawler. 1973.

The anchovy is a small, almost pathetic, fish that has a luxurious silver shimmer which appears much more elegant than their humdrum status. They arrive to us, mostly, in the same form as their living animal body unlike other common staples, such as a cow that is transformed into beef and steak, or salmon fillet. The anchovy is just called an anchovy whether it’s alive in the wild, whole and ready to be eaten, or processed into a paste. If you encounter them at all, it is likely in a painting or inside a tin can. It’s obvious why an artist would be drawn to depict them – the flickers of white and grey and green and blue are unusually striking in a domestic scene, especially if it is set within a humble home with a pale brown table and scuffed tableware.

While they are not exactly at the bottom of the food chain, they’re as close as a fish could be. Anchovies feed on plankton, a loose category of organisms that include bacteria, algae and microscopic fungi (So lowly is this prey fish that they can only feed on those that are unable to navigate the waters themselves and depend on the currents for movement). Although they must still fight a brutish existence to make something of their short life – when an anchovy egg is laid, its larva has a limited amount of yolk from which to feed and a high metabolism for any movement. If its first morsel of food requires even a few wiggles to consume, it will likely die. And since the eggs are laid in great quantities, and require even greater quantities of plankton to live and grow, they enter the world with a statistically grim start.

They eat rudely and without distinction: mouth open while swimming, swallowing all that drifts towards them. The inside of their mouths are terrifying, and it’s lucky for the plankton that meet their doom inside it that they lack any significant consciousness that might be able to grasp the horror of the anchovy’s gill rakers, the bony comb-like mini-teeth that filter food from dirt (think of the giant monstrous sand worms shown in sci-fi movies such as Star Wars or Dune).

Numerous categories and subtypes are applied to the anchovy, but the most accurate term to me seems to be forage fish. The prey and bait of others, a small body and large family is more than a metaphor – it’s a defensive strategy. Another fish might find them too fast or small to catch, or be worth pursuing too singularly, and even if a dozen or so are eaten then the school of anchovies, that can vary between a few hundred to the millions, will survive.

A school of anchovies can be a troublesome thing. In 2014, Californian’s encountered a strange sight: an almost biblical dark swarm along the San Diego coast. While not a sign of the end times, it was equally mysterious and foreboding – scientists were perplexed by why the anchovies had swarmed so close to the shore, and still have little of an explanation. Robert Monroe, a communications officer at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, quickly ran to the site with a GoPro camera to capture what was happening. "It was remarkable. From a distance it looked like an oil slick and you think 'What happened?' and then you get up close and it's amazing ," he told the Los Angeles Times. "It's like watching the motion of a lava lamp." David Checkley, a Professor at Scripps, estimated there were between 1 and 100 million fish in the school; it appeared on Monday and had all but disappeared by Tuesday. It was the warmest water (74 degrees) they had ever been recorded in.

Oceans, seas and bodies of water around the world are their home – they prefer to live and swim in temperate waters, but have also been found in colder climates. They thrive in the Mediterranean, especially in the Aegean, Alboran and the Black Sea, and can be found in the waters around Crete, France, Greece, Italy, Northern Iran, Portugal, Sicily, Spain and Turkey, and even along the coast of North Africa. Naturally, the anchovy features heavily in the cuisine of seaside towns where they are a cheap and convenient source of protein, saltiness and umami. Their earliest ancestors can be traced back to two fossils from the Palaeogene period in disparate locations: one in Belgium and another from Pakistan.

The people of Naples found abundance and proximity in the anchovy when they first added it to pizza in the 16th century, which was often paired with tomatoes to balance the saltiness of the fish. The strength of the anchovy flavour often had to be navigated like this through its history – the first usage by the Romans was as Garum, a fermented fish sauce that is used as a condiment. Kept in enough oil and salt, an anchovy can be preserved for a remarkably long period of time. As Italian food was brought to the United States from the 18th century, traditional ingredients were modified and tweaked until eventually being replaced by local tastes. Usurped by onions and pork, the unpopularity of anchovies on pizza became a kind of running joke that eventually manifested as a movie plot – in Loverboy (1989), a pizza delivery boy offers his services as a male escort when customers use an uncommon codeword: ‘extra anchovies’.

Strong in taste, the anchovy is an ingredient that warrants subtle handling. Take its role as a topping on pizza, for instance. In traditional Neapolitan cuisine, fish is not usually mixed with cheese. And as the anchovies would have been stored in salt and oil for extended periods of time, it was common to wash off the salt brine before adding it to the pizza. While now it’s more typical to add tinned anchovies, which don’t require additional cooking due to the curing process, simply adding them to the pizza after it comes out of the oven is enough for the anchovy to melt slightly and become aromatic.

Sometimes, a handful of anchovies is all you have (or need). The playwright and politician Richard B. Sheridan was famously once locked in a room with a pile of anchovy sandwiches and some papers until he finished writing a play. In other moments in time, the availability of anchovies was not a certainty: In 1972, overfishing of one of the most important single fish – the Peruvian anchoveta – reached a crisis point. Small in size, the Peruvian anchoveta is a species of anchovy found within the Southeast Pacific Ocean and is the single most commercially significant fish in the world – sometimes representing up to 15% of global fishing. The Peruvian anchoveta played a supporting role for other more commercially viable livestock, being transformed into meal, even for salmon. Since World War 2, demand for food soared and the Peruvian fishing economy rode that wave, until they couldn’t anymore: from the fishing season of ‘72 the supply collapsed and remained low throughout the decade.

‘Coastal Peru is normally a cool and misty land,’ wrote C. P. Idyll in 1973 for Scientific American, before crediting the El Niño, an irregular and unpredictable shift in the earth’s ocean currents, as the cause of the crisis. The El Niño describes a cooling phase across the water surface and air temperature; La Niña refers to a warming. It is not related to what is commonly referred to as global climate change, although it does technically describe changes in the climate on a global level.

The first sign that the El Niño has arrived is a slow but stubborn increase in the water’s temperature. The second sign is the arrival of fish that prefer warmer climates – the yellowfin tuna, the dolphinfish, the manta ray and the hammerhead shark – many of which feed on the anchovy. But predators are the least of the prey’s problems: the real impact of the El Niño on the anchovy is how changes impact their food supply. Previously, the northbound Coastal Current would bring waters from deep in the ocean closer to the surface, thereby bringing more plankton into swallowing distance. As this slows, or even halts, ‘the delicately adjusted world of the anchovy tilts.’

The fishing industry strained the anchovy ecosystem. Small technical innovations (nylon nets) and ever-growing numbers of boats grabbed and exported everything they could. American and European consumers wanted more. By the 1970s, the anchovy represented around a third of Peru’s income from exports. Beginning in earnest from ‘57, a dozen or so factories popped up as did a vibrant parallel economy, but only a few years later the government, backed by a grant from the UN, began to study – and eventually regulate – the supply out of fear of exhausting the resource.

It is expected that the climate crisis will repeat the warming process – with disastrous results. Renato Salvatteci, a biologist at the Christian-Albrecht University of Kiel who researches fisheries, conducted a study in 2008 to test what this might look like. A research vessel extracted a 14-meter-long core from Peru’s sea bed in 2008; what was removed could be dated back to 116,000 and 130,000 years ago, mostly consisting of anchovy bones amid about 100,000 vertebrates, an earthly relic from a time when the earth was warmer than now. By studying the sediment, he could sketch a vision of what might unfold. Warmer water contains less oxygen, resulting in smaller, less nutritious fish. The anchovy is not suited to these conditions, meaning they are likely to be replaced by others smaller than themselves. His conclusions were modest: instead of using the Peruvian anchoveta as meal for other species, like salmon, we’d be better off eating them directly ourselves.

While a warming planet threatens the anchovy, they’ve also taken on a new importance for climate-conscious consumers, and are increasingly being marketed as such. Where other animal proteins, such as beef, have been highlighted as having a major environmental cost (around 56kg CO2 per edible tonne), tinned fish is just a fraction of that (between 1-6kg, depending on the species). New technologies are being developed to create synthetic proteins to replace farming, but old techniques like tinning are being looked at in a new light. Wild fish require little to no intervention other than being caught, and once canned they require no refrigeration; food waste is a non-issue, too.

Canning fish is in its own way a response to the environment – a modern intervention to make nature yield to convenience. When Nicolas Appert first developed a precursor to the process, long before the science of bacteriology would explain how it could work, a local paper reported that he had: “found a way to fix the seasons; at his establishment, spring, summer and autumn live in bottles.”