Wrestlers by Thomas Eakins.

I didn’t expect there to be so much cottage cheese. In the world of online gym and workout advice, a special emphasis is placed on high-protein foods for a number of interrelated reasons. The first, perhaps most obviously, is the relationship between protein and building muscle. On multiple forums, the science is explained at length by amateurs to each other: the process of muscle growth involves hypertrophy, where the muscle is pushed to breaking point and ‘rips’, which can then be filled by protein thereby building a new, stronger and expanded muscle.

A second more subtle advantage that protein offers is how it satiates the appetite, supporting weight loss goals. You don’t just want to bulk; your mass must be lean. Protein is a ‘complex’ nutrient and takes longer to break down. All foods are not the same despite what macro numbers might lead you to believe: a croissant and an unseasoned chicken breast are around 250 calories, one person opined, but eat two of the former and you’ll be hungry again in an hour.

One recipe did a lot of work to seemingly obscure the cottage cheese. A kind of beef burrito with the standard onion, spices and beans also involved a faux-cheese mixture of scrambled eggs and cottage cheese. The ratio of fat to protein was high, and the soft texture of the mixture mimics the satisfying ooze of fast food – it’s enough like the real thing while ticking the correct boxes on your food tracking app.

Peanut butter is a common go-to ingredient, but dig a little deeper and its credentials become less convincing. The amount of protein is good, but it’s often high in sugar and therefore isn’t as efficient (food, workout routines and lifestyles are regularly quantified through their relative efficiency). The hardcore advice doesn’t come through comments, videos or recipes, but in spreadsheets and that’s where the myth of peanut butter was first busted for me; spreadsheet discourse is on another level. I don’t know if any of this is true; I am fascinated by how communities are drawn together not just by an activity or interest, but a set of truths that are claimed and repeated with enthusiasm.

I think it is easy – if not a little trite – to disparage the gym bro, like a fish in a barrel they are a commonly agreed target, with much of society's ills laid at their feet. So much so that many men who attend the gym will also poke fun at the caricature to make it clear that they are different, despite their own penchant for tracking calories, reps and routines, while many women who workout will ironically identify as such.

Similarly too, the culture of self tracking is quickly equated with other metric bound systems and their faults: the relentless call of the to-do list, the inhuman pace of capitalism, the cruel indifference of bureaucracy. Ultimately a food or fitness app introduces an element of gamification and impersonal guidance, adding direction to what can often feel like the seemingly impossible task of changing your body.

All this might echo the ‘toxic’ traits of shallowness, productivity and gambling. We look at ourselves in judgement, we only feel good when meeting some arbitrary standard of goodness, we chase a dopamine high despite its short termism. In response, the culture of gyms and workouts have developed a new vocabulary for itself. Terms like weight loss are obscured with euphemistic references to body image; strength is substituted for emotionally oriented goals like mental health. The recovery benefits of protein are emphasised over its role in muscle growth.

What is interesting about the cultural phenomenon of these gym-specific recipes is not just the emphasis on macros, but it’s often explicit about who the audience is. Not just men, but men who are also new to cooking with any level of intention. Going to the gym has framed the act of cooking and the needs of nutrition in a different light, both obviously gendering it in a way that makes sense to them, but also compelling them to want more from a meal than simple alleviation of hunger. These recipes must navigate the complexity of health for a wide array of people while also introducing a new skill set, and don’t forget the emphasis on convenience too. It’s rare for any of these recipes to take longer than 30 minutes, and they are almost exclusively made to be meal prepped on a low budget. “That is 50 grams of protein for just 80 cents a portion”, they might say.

A lot of food culture online promises to not compromise flavour and health while also being convenient, made from simple ingredients and cheap. The pitch is typically low key: easy midweek meals and healthy food that actually tastes good. A truly extraordinary boom of food-related content has boomed over recent decades, beginning with a handful of sought after cooking books, a slow rise of the TV chef, to now a seemingly endless stream of digital content produced by self-taught home cooks and experts alike. Quietly, without admitting it to themselves or their audiences, the gym bro is also a kind of food influencer.

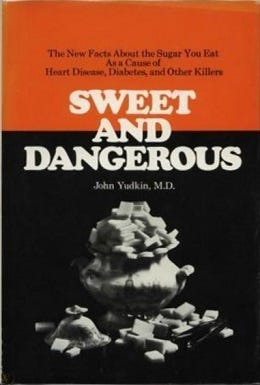

Nutrition is a thin science. Before the 20th century, it was a secondary concern of chemists and only became a distinct field in a relatively short space of time. One of the first university courses was established in the 1950s by John Yudkin, a British physiologist who would later write popular books on weightloss such as This Slimming Business (1958) and Pure, White and Deadly (1972).

Pure, White and Deadly, as you might reasonably assume, was about sugar, and has since become a kind of symbol of the poor science that underpins scaremongering about diets. Yet fear is a powerful motivator; it feels instinctively true that the pleasure of food might come at a cost. ‘There are few of us today whose eating habits have not been influenced by the work and the words of John Yudkin,’ reads one his obituaries, summarising his remarkable career and continuing influence.

Yudkin’s ideas can be traced back to Dunn Nutritional Laboratories in Cambridge, an early research institution that was originally founded to study vitamins, the focus of its first director Frederick Gowland Hopkins, who was co-awarded the Nobel Prize in 1929 for their discovery.

The early history of nutritional science was, according to Kenneth John Carpenter, “the vitamin era”, and in Britain especially, the new science attracted significant institutional attention, including the Ministry of Food, the Ministry of Health, the Medical Research Council, the Cabinet Advisory Board on Food Policy.

The lack of uniform standards was a subject of concern to Yudkin: despite this interest, there was little attempt to draw coherence between efforts to improve public health. Much of his research found overlaps between poor health and social status, drawing an economic link to poor nutrition. Supplements did little to amend social inequalities, rendering the relationship between nutrition and society more complex. When he had the chance to make a change, as the Chair of Physiology at Queen Elizabeth College, he took it, creating the first university degree in nutrition in 1945, combining chemistry and biology with psychology, sociology and economics.

Yudkin’s public reputation soared as food rationing policies of World War 2 came to an end. When else could be a more perfect time to study the impact of food, particularly previously restricted ones like sugar, than at a time when millions of people suddenly had renewed access? It was as if all of the USA, Britain and Europe became a single study, and faced with a remarkable rise in heart conditions and obesity Yudkin found his culprits. His book the Slimming Business took aim at carbohydrates, with later books – Pure, White and Deadly – updating the thesis to wrangle with sugar. The historical backdrop of consumption and efforts to control it invariably take on a semi-religious dimension: gluttony or vanity, your choice.