Ed Ruscha

I can feel the sun on my feet from the asphalt because I'm wearing sandals. I shuffle through a parking lot because that’s what you do here. The charcoal gray has taken on a slight yellow hue, the distance blurs from the heat. Cruel like a desert, the standard parking lot is hot, dry and unforgiving.

People wander through parking lots, dragging their bodies without any hope of finding respite along the way. Accidents tend to happen here because people believe it is safe, or perhaps they don’t believe it is a real place at all.

Asphalt is the dominant material of choice, despite its inherent inhospitality – it is cheap, can expand and contract with the weather, and allows water to easily drain off. The asphalt, the uncompromising flat planes, the undecorative scale, the raw functionality, all the aesthetic components of the parking lot are born from industry, yet it lacks the underlying utopian vision that undergirded other vestiges of modernism. Like a machine for living, the parking lot is a void for shopping.

Writing about cars, urban space and America used to talk about the journey – the first essay of this sort I remember reading was Christoper Hitchens’ The Ballad of Route 66, although Hunter S. Thompson’s shadow clouds the genre – and in recent years, writers increasingly expresses a perverse fascination with motorways. Rebecca Solnit reflects: ‘when I got home I would find that the hours I’d spent negotiating freeway merge lanes and entrances and exits and parking garages was, in some mysterious way, more memorable than the museums. I was supposed to have a head full of paintings or installations, but instead, I was preoccupied with the anonymously ugly spaces that are not on the official register of what any place is supposed to be.’

Parking lots are a space that are as ugly to experience as they are to think about. The best argument for parking lots is to consider them as vestiges of pure modernism. The Futurists would hate them, of course, as the parking lot is where machines slow down and stop, not to achieve superhuman speeds. They are modest, domestic. Connected to the car-led revolution of urban space, parking lots – specifically those that are open, flat and made from asphalt, not multi-storey garages or ad hoc meanwhile spaces – are not just products of the 20th century, but speak to one of its overlooked tendencies: non-utopian modernism.

I am not walking through an anonymous non-space of globalisation, but a semi-suburban parking lot in a secondary city of Florida. American in more ways than one, the parking lot appears to me as the unofficial monument of the country, differing from its established icons that explicitly borrow from an old European tradition of architecture, namely Roman and Greek. Baudrillard said that Disneyland was invented so people will believe America was real. By contrast, we don't evaluate or judge the parking lot. It is so boring as to barely register: our eyes look for a spot then immediately turn our attention to where we are going next.

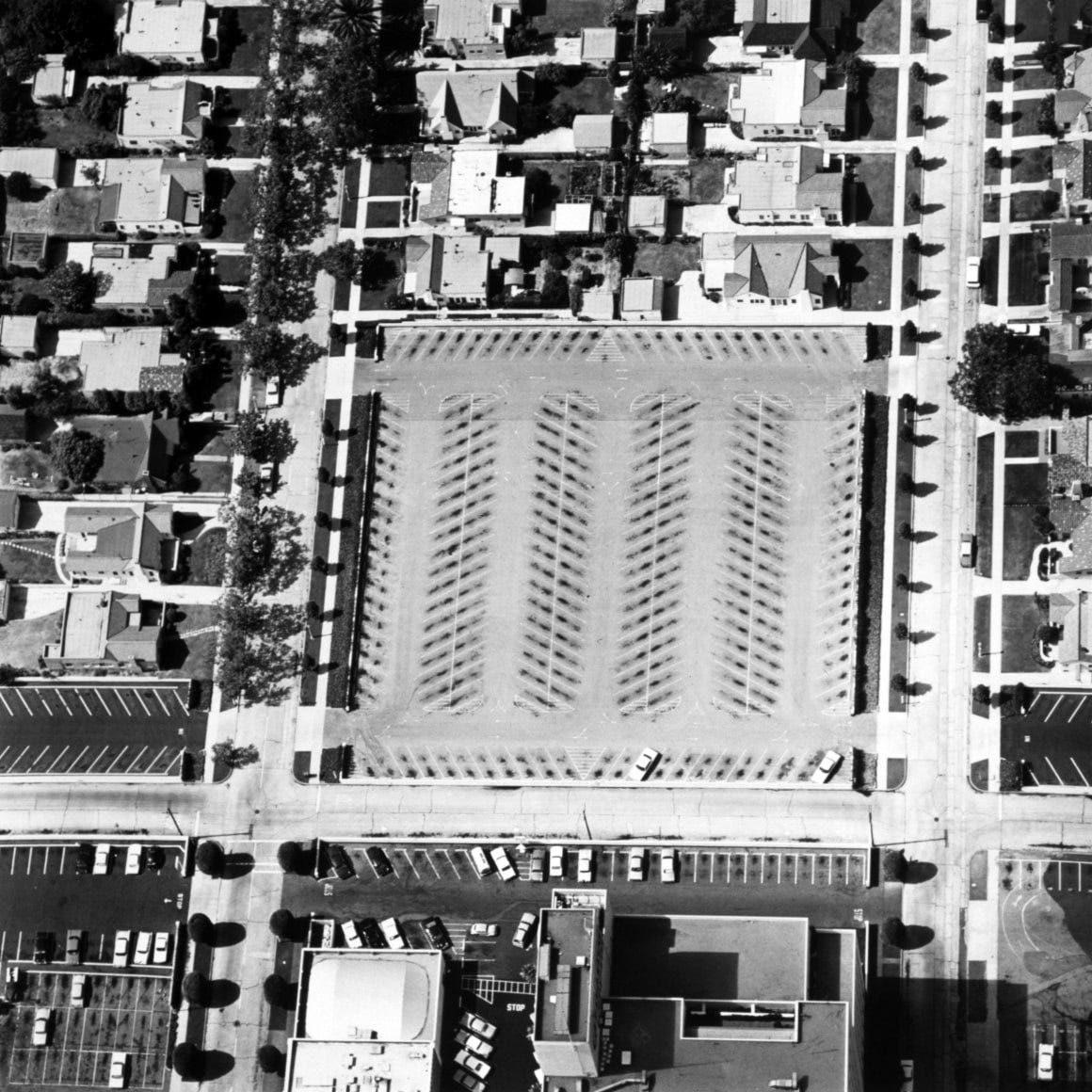

Guy Debord once claimed ‘the final form of commodity fetishism is the image’, and who takes better images of parking lots than Ed Ruscha? His are Californian, specifically from Los Angeles, where the romance of traveling the vast expanse of America typically ends.

Ruscha’s series is dated to 1967. He published 30 or so photographs taken by Art Alanis during a helicopter ride around Southern California early on a Sunday morning, capturing the growing urban sprawl of the city in a distanced, deadpan style. Caught through an aerial view, it is perhaps the only way to actually see a parking lot without simply looking through it.

I admire parking lots, but I don't like them. In fact, I hate them. But you have to admit: A tremendous level of order is achieved by the most modest means. Paint in a simpler, rectangular grid pattern manages the flow of people and machines, made all the more effective by its seemingly crude appearance. There are few other innovations possible.

The addition of payment mechanisms in the contemporary flat and open-air parking lot ruins what idiosyncratic beauty it can legitimately claim, often necessitated by the privatization of public infrastructure. That being said, the parking lot is not a result of social democracy and the wider orientation of cities around cars speaks to a totalitarian alliance between narrow notions of individualism and interests of the automobile industry.

As an architecture, the parking lot is diffuse and impersonal, even more so than the corporations attached to them. Each franchise of the chain may be identical to each other, but there is a singular character that they replicate, a brand they work to create. The parking lot, by contrast, is broadly similar regardless of its context. All corporations compete, all corporations share the parking lot.

Some reading

Urban designer Eran Ben-Joseph charts the evolution of the humble parking lot.

https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/brief-cultural-history-of-the-parking-lot/

Fredric Jameson talks about Rem Koolhaas and the future of the city for New Left Review in 2003

https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii21/articles/fredric-jameson-future-city.pdf

Also in New Left Review, an interesting reflection on Marxism, green politics and infrastructure in contemporary Japan through an interview with Kohei Saito

https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii145/articles/kohei-saito-greening-marx-in-japan

And ‘Check out the parking lot’ by Rebecca Solnit in London Review of Books

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v26/n13/rebecca-solnit/check-out-the-parking-lot